This article was first published in the Spring 2017 edition of the Sikh Education Council’s ‘Sikh Sunehan‘ quarterly publication. In the interests of reaching a wider audience so that learned responses can be garnered, it is being published here on naujawani in a digital format with the approval of the author.

It is evident from Emperor Jahangir’s autobiography Tuzk-e-Jahangiri, that Mughal officials had gathered intelligence on the momentum with which Guru Nanak’s revolutionary movement was sweeping across the land. In their eyes, Guru Arjan Sahib’s activities were radically subversive, socially revolutionary and politically dangerous for the Empire. The socio-political landscape in South Asia was being challenged and this had clearly rattled the higher echelons of the Mughal regime. They had recognized the parallel power structures being created by the House of Guru Nanak Sahib.

The Mughal authorities observed how the Sikhs venerated Guru Arjan Sahib with symbols of royalty, for example, the use of a canopy, a throne and the waving of the chaur sahib (whisk) over his head. They knew about the city of Ramdaspur, which like Kartarpur, Khadur Sahib and Goindwal before them emerged as a new ‘power center’ where Guru Arjan Sahib had established halemi raj (divine rule of justice and humility). The citizens of this town enjoyed comfortable living, fired with the spirit of fearlessness, dignity and self-respect. Sikh bards sang eulogistic songs of the majesty of the Sikh court using overtly regal metaphors.

ਤਖਤਿ ਬੈਠਾ ਅਰਜਨ ਗੁਰੂ ਸਤਿਗੁਰ ਕਾ ਖਿਵੈ ਚੰਦੋਆ॥

Guru Arjan sits on the throne; the royal canopy waves over the True Guru-Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Bhatt Satta & Balwand, Raag Raamkalee, Ang 968

(English interpretation by Sant Singh Khalsa)

Guru Arjan Sahib had established a treasury too by reorganising the Masand system initiated by his predecessors. Under the Guru’s direction the Masands not only collected taxes but also taught tenets of Sikhi and settled civil disputes in their locality. The funds were then used to finance and run the Guru’s institutions and infrastructures to further his governance.

ਗੁਰ ਅਰਜੁਨ ਕਲੁਚਰੈ ਤੈ ਰਾਜ ਜੋਗ ਰਸੁ ਜਾਣਿਅਉ॥੭॥

So speaks Kalh the bard, O Guru Arjan you know the essence of political rule |7|-Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Bhatt Kalh, Svaiyay M5, Ang 1407

(English itnerpretation by Sant Singh Khalsa)

Sikh tradition holds that before his execution, Guru Arjan Sahib had already instructed his son and successor to take up arms, and resist the tyrannical rulers of South Asia. Having built the foundations for resistance, Guru Arjan Sahib had already initiated the next phase of building what historian J.D Cunningham termed a ‘State within a State’ when he started purchasing and trading in horses and weaponry for the purposes of arming Sikh military units. Furthermore, scholar Max Arthur Macauliffe asserts that whilst in captivity, Guru Arjan Sahib sent a command for his soon-to-be successor Guru Hargobind Sahib to: “sit fully armed on his throne and maintain an army to the best of his ability“.

As a result of the Guru’s political activity, Jahangir felt an immediate threat from the early achievements of the Sikh Panth. His response was to try and bring an end to the Guru’s endeavors, which in effect is why the Guru was imprisoned in the Fort of Lahore. Jahangir gave orders to Murtaza Khan, the Governor of Lahore, to firstly confiscate the Guru’s possessions and assets, and then to execute him.

On 24 June, Sikhs from across the globe will seemingly commemorate the martyrdom of Guru Arjan Sahib by holding shabeel – a tradition of serving sweet, cold drinks to the public, allegedly done by Sikhs following the immediate aftermath of Guru Arjan Sahib’s martyrdom. The rationale for this tradition is firstly presented as the need to recognise this martyrdom as the ‘sweet will of God’, and secondly the serving of sweet, cool drinks as a display of chardi-kala, presumably Sikhs taking an attack on the House of the Guru as an opportunity to spread positivity.

It is unclear however, where this tradition was first recorded in Sikh history, if anywhere at all. As such, questions arise regarding the authenticity of shabeel. There is no mention of it from early Sikh writers such as Bhai Gurdas Ji, Rattan Singh Bhangoo or even Kavi Santokh Singh. Furthermore, British historians as well as European and Mughal historians do not appear to mention it in their accounts. Moreover, the activity becomes problematic when one considers the logic behind the explanation given for shabeel today – as a response to the Guru’s martyrdom – especially in light of the socio-political climate of that time. Today, a concerted effort is made to raise awareness about this peaceful Sikh response which somehow illustrates chardi-kala. It is imperative to question why so much attention is being placed on highlighting an event for which there is no historical record of having taken place.

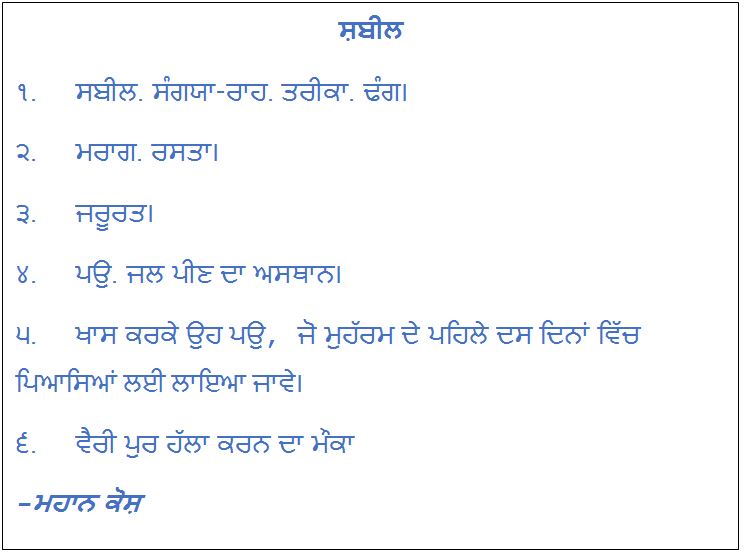

The only documented reference is one given by Kahn Singh Nabha in his Sikh encyclopedia, ‘Mahan Kosh’. In this, shabeel (ਛਬੀਲ) is said to be an Arabic word in origin, which in the literal sense means path, technique or necessity. It is also a general term used to describe a place where water is served. It must be noted here that the term is therefore not exclusively linked to the martyrdom of Guru Arjan Sahib. Shabeel can be found running all year round at Darbar Sahib where cold water is served.

Interestingly, Kahn Singh Nabha gives importance to the term when talking about muh~rm (Muharram). This is the first month in the Islamic calendar and it was during the month of Muharram when Husayn ibn Ali (grandson of Muhammed) was killed during a battle in the year 680. It is recorded that shabeel was then handed out to all those that had gathered to remember him. It is believed that this happened during the fasting period which is why only water was served. Kahn Singh Nabha does not relate the term to the martyrdom of the fifth Guru Nanak. Some would suggest therefore, that the tradition of shabeel was borrowed from Islamic history and at some point, aligned with the remembrance of Guru Arjan Sahib’s martyrdom. This further substantiates why there might be no mention of the tradition from Sikh historians or foreign chroniclers.

So how does the martyrdom of Guru Arjan Sahib become associated with the term shabeel? Perhaps the answer lies in considering the final interpretation of the term in the Mahan Kosh. The final interpretation of the term is that shabeel implies an opportunity to attack the enemy. This interpretation offers the most logical explanation of why and how the term became synonymous with the martyrdom of Guru Arjan Sahib.

This perspective is in line with Guru Hargobind Sahib’s tenure as Guru. Does he commemorate the martyrdom of his father by handing out cool, sweet drinks to the public as a show of chardi-kala? No, he adorns two swords, raises a royal throne at the Akal Takht, mobilises the military units under the Akaal Sena and declares war against the Mughal establishment. This is the real shabeel that took place in 1606 and the embodiment of chardi-kala; when faced with the threat of annihilation he continues to further Guru Nanak Sahib’s mission as per Guru-maryada.

This type of action, spearheaded by the Guru himself, has inspired generations of Sikh to respond to attacks on the sovereignty of the Panth in many differing ways. However, the rhetoric of using an attack as an opportunity to serve others is rather troublesome to Sikh psyche because a Sikh does not need an excuse to serve, rather s/he serves entirely off his/her own volition. On the contrary, if any seva took place following the martyrdom of Guru Arjan Sahib, then it came from the political achievements of the Guru’s Sikh in the continued pursuit of Sikh sovereignty for the establishment of halemi raj, as prescribed and lived by Guru Arjan Sahib himself.

There was and is undoubtedly good reason for serving sweet, cold drinks during the hot months of a Punjabi summer, particularly to an impoverished populace that all too often goes without. It is similarly of little doubt that the Sikh community would be the obvious harbingers of such an activity. But how this has been related to the martyrdom of Guru Arjan Sahib shows a wilful ignorance, in the modern era at least, of what came next under Guru Hargobind. Moreover, the manner and need for undertaking shabeel in the west is of great concern; where sweetened butter milk, rose water and ice blocks were served as a delicacy on the subcontinent, soft drink beverages mass manufactured by corporations are arguably being given away in the name of the Guru for the purposes of public relations.

In conclusion, the shabeel narrative that is disseminated today seems rather inconsequential when we consider Guru Arjan Sahib’s political achievements that led to his martyrdom and the movement carried forth by our Guru Sahiban and subsequently the Khalsa Panth. The question we must ask ourselves today is, should we encourage a tradition that may or may not have taken place in the spirit of merely raising the Sikh profile?

If we are looking to merely raise awareness on a display of chardi-kala then we have centuries of documented Sikh history that is full of such Guru-inspired action. Only 24 years ago on 9 October 1992, when Sukhdev Singh ‘Sukha’ and Harjinder Singh ‘Jinda’ were executed by hanging in Pune Jail, the Sikh Panth accepted their final requests and rejoiced in their defiance against the oppressive Indian establishment by handing out sweet ladoo. It was a celebration of their resolve and determination, that no power could break their allegiance to the Guru. That is chardi-kala, and if a shabeel of sweet, cool drinks was handed out in 1606 then it was done as a celebration of the Guru’s political conquests. It was done in a show of defiance from the Guru’s beloved that the establishment may have destroyed his physical frame, but his spirit was with them and they would continue forth with the Guru’s mission, come what may.