As the European football season draws to a close, some of the most important matches determining the outcome of league and cup competitions worth hundreds of millions are taking place. Fans of all clubs sit up sharply and hold their breath in anticipation of a moment of magic that will be remembered for decades to come, just as broadcast and press media outlets intensify coverage on and off the pitch. It is in this context that a game of great importance in Spain last Sunday night continues to make the headlines – but for all the wrong reasons.

One of the most exciting and decorated teams of recent years, FC Barcelona were playing an away match at Villareal on the east coast of Spain. With the score poised at 2-1 to the hosts, Brazilian full-back Dani Alves went to take a corner kick. Having made the instrumental shot which led to Barcelona pegging the score back from two-down courtesy of an own-goal, Alves would have been on a high and eager to take the set piece when a banana was thrown from the crowd in his direction. The intention of the gesture which is not new to Spanish football, or many other football stadiums in Europe for that matter, is to depict the black player as a monkey. I can only wonder at the feelings that go through a player’s mind at that moment, insulted so publicly, surrounded by your peers and tens of thousands of fans – anger, disappointment, confusion? It would be perfectly forgiveable had Alves turned around to face the crowd and lost his concentration for a moment, but what he did next has helped the incident to stand apart from previous ones – he peeled back the skin and took a bite whilst positioning himself a few steps back to take the corner. Not only did he continue to play without losing focus – he was the instigator of the equaliser, again an own goal resulting from a cross he played into the box – but he made a statement to the act of racism which had targeted him.

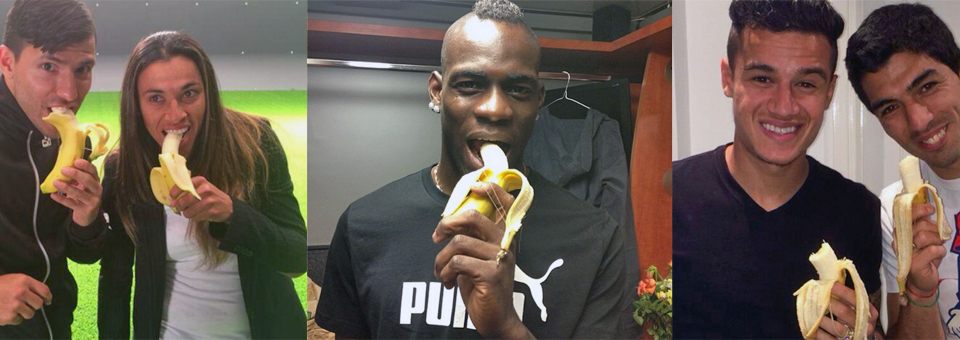

A number of high profile footballers have taken to social media to show their support for Dani Alves and to reiterate that racism has no place in civilised society. Black players have been part of the professional game for many decades in Europe now, but continue to suffer from racism in the stadiums and boardrooms alike. It has not gone unnoticed that there are no black managers in English football (professional leagues) who will finish the season in their posts; there were only five at the start of the season as it was. Proof if it were needed that whilst society in the UK and the ‘developed’ nations of the west are bastions for equality, much is still to be done if minorities are to be treated as real equals.

It’s impossible to discuss the issue of race in football and not make mention of the continuing dearth of professionals from a South Asian heritage, particularly when an incident like this highlights how far society has not come. Bangladeshis, Indians, Pakistanis, Sri Lankans and Punjabis are all conspicuous by their absence on the pitch. There were only 8 homegrown Asian players with professional contracts earlier this season, a statistic made more stark by the considerable passion which South Asians clearly have for the game in the UK. When I was growing up, we were often told by our white peers and even on one occasion a school PE teacher that racism wasn’t the only thing holding back Punjabi kids from becoming footballers – we were meant to do other things like run businesses and go to University (it was meant as a compliment, I think). But I knew that wasn’t true. Firstly, my father wanted nothing more for my brother and I to become professional footballers. He had himself been the solitary brown face in all-white Sunday league team line-ups in North Hertfordshire in the late 60s and early 70s so it was no surprise he wanted us to fulfill his dreams. Secondly, I was unfortunate enough to witness first-hand how much we were really ‘wanted’ in professional football. My best friend whilst growing up was an awesome player and was selected for County teams throughout our first few years of secondary school; that all changed when we reached our senior years and schoolboy football became serious. Not only was he no longer selected to start, but other players on the team went out of their way to make him feel like he was not welcome – a deep-lying pain that surfaced in our later teen years when we encountered some of those ex-fellow footballers on a night out and he struck out at them, releasing years of frustration.

Change is coming, we’re told, and the Football Association in England has a number of plans to boost South Asian numbers at every level. Their desire is welcomed and the creation of permanent posts to manage inclusion projects might one day bear fruit, but in the meantime it is more likely that professional players of South Asian heritage will come through grass roots projects like those of the Khalsa Football Academy (KFA) – a movement I was also lucky enough to belong to in my formative years. Funnily enough, the KFA travelled to Valencia in Spain a number of years ago following racist chanting by Spanish supporters in a high-profile international match against England and whilst Spain is not the only European country with inclusion problems in their game, it does make you wonder how much abuse non-white players have taken in ‘La Liga’ without a significant reversal. The fan who threw the banana onto the pitch at Dani Alves has been identified and banned for life by Villareal sending a serious warning to anybody who thinks that they can use football to give voice to their own shortcomings and prejudices. But that doesn’t even begin to tackle the real problem of exclusion in football.