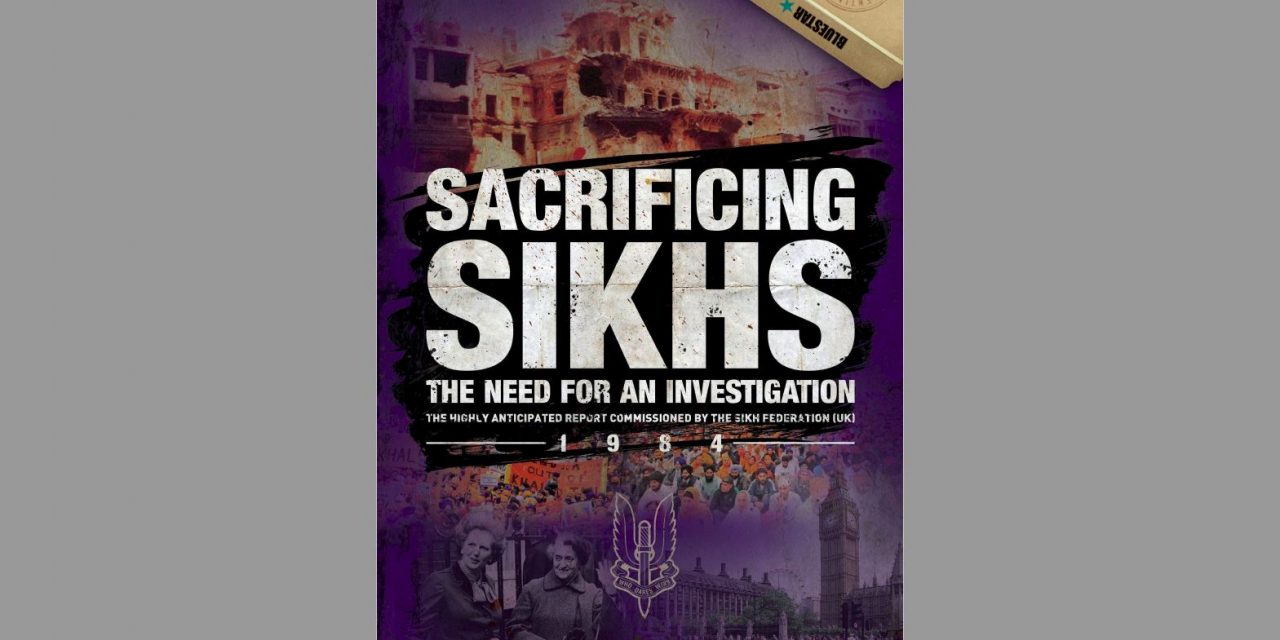

A long-awaited report exposing the British Government’s role in the 1984 invasion of Darbar Sahib Amritsar was released this week titled ‘Sacrificing Sikhs’. Commissioned by the Sikh Federation (UK), the research and compilation was undertaken by freelance journalist Phil Miller and stakes the claim for an independent public inquiry. The document was released at an event at the House of Commons on Wednesday 1 November that was attended by prominent members of the Sikh community as well as Parliamentarians, and is now available to download and read in its entirety at the Sikh Federation (UK) website. Having spent an entire day reading the report thoroughly, I present here why it should herald more than most would think.

In January 2014, a series of letters depicting UK-Indian relations around the year 1984 were released to the public at the National Archives in London. They spread rapidly across social media leading to questions on the role played by the Thatcherite Government in the invasion of Darbar Sahib, and particularly the advice proffered to the Indian Armed Forces by an SAS Advisor. The resulting internal review conducted by Cabinet Secretary Sir Jeremy Heywood, largely cleared the then British Government of colluding with the Indian authorities to plan and orchestrate the killing of thousands of civilians in the Sikh World’s epicentre. Widely met with ridicule from the UK’s Sikh community, that ‘internal inquiry’ was merely a formality whose conclusions were unsurprising and gave short thrift to the deep relationship many knew existed between the two states, and their respective leaders Margaret Thatcher and Indira Gandhi.

In the three years since, the Sikh Federation (UK) have not only led the call for an independent public inquiry, but also commissioned further research into the archives to build the case as to why this is needed. The fruits of this investment can be found in the report which provides an exposition of just how deeply embedded the British Government was in developing certain elements of the Indian Armed Forces. There is an immense level of detail that brings into sharp focus the commonly understood argument that the UK stood to benefit from trade with India, if they could provide financial aid and support for military development. At sixty pages, sadly not every Sikh passionate about current affairs is going to read through the entire report, but I would highly advise doing so as it provides a number of previously unknown insights. These concern related issues and not just the invasion of Darbar Sahib:

“One of the FCO’s ‘sensitivity reviewers’ in 2015, Bruce Cleghorn CMG, who was tasked with censoring many of these old documents, was a diplomat at the British High Commission in Delhi in 1983 and the South Asia Department in London in 1984. In many cases he had the task of censoring documents he wrote himself.”

“At a meeting with Thames Television, a production company that was making a documentary on abusive regimes, the FCO hoped to dissuade one of the programme’s producers from including India in the show: “We tried discreetly to head her away from India” (PAGE 17)

“The British High Commission told Geoffrey Howe on 5 July 1984 that the Indian government “are said to be thinking of forming a new para-military National Guard with specific responsibility for combating internal terrorism.” (PAGE 36)

In the opening pages of the document, the executive summary states that: “This report is a modest attempt at truth recovery and better understanding the legacy of a bitter conflict.” In this regard, it is vital that research like this is undertaken and published so that the reality of the State many of us call home is aired for the record. But unless we begin to interpret what this says about our citizenship of this State, how these findings impact our concept of nationality, and what it means when we say we ‘belong’ to this country, the report and any future inquiry is futile. I do not oppose the Sikh Federation (UK) demand for a full public inquiry, but I have previously asked the question of what we think will lead to if it were conducted; my interest lies in the answer to that question, which arguably we could start to answer today. Our comprehension of what went on would be enriched, perhaps some introspection by British Parliamentarians would follow, and who knows – maybe even an apology would be proffered. But mark my words, if the same opportunity arose after that to support the Indian State in a crackdown on Sikhs in Punjab, and some benefit to the UK would follow, neither a Conservative, Labour or any other political party-led Government would hesitate. It seems we don’t want to recognise the nature of this game; perhaps that is why we Sikhs do not possess a sovereign state of our own.

Of some 23,000 documents concerning UK-Indian relations at that time, only a paltry 200 have been released to the public, many containing redactions. Whilst this will be of great annoyance to the Sikh community worldwide, I would like to hope that the Panth could learn an important lesson at this moment: sovereign states owe nothing to anybody. I was born in the UK, live in the UK and am a UK passport holder; but I have never been under the impression that this country has my best interests as a Sikh at heart. It is imperative that Sikhs, wherever they reside, ask what it is that their adopted State stands for. In the UK, we need to have a greater appreciation for what this country has done and continues to do around the globe through political interference, benefitting from conflict. It might feel awkward for those of us with UK passports, but how are we any different from Sikhs who reside in ‘India’ – a State whose coming into being was never endorsed by the Sikhs? Why are we afraid from asking these questions? We cannot and should not shy away from the opportunity afforded to us with the publishing of this report to look deeper into what it takes and means to be in power, and how we could apply that to our Panth. I would urge every Sikh forum, platform and space to present an analysis into the findings presented in this report, and not to limit the scope of our conversation into seeking redress from the State – but asking why we are having to make such a request at all.

‘Sacrificing Sikhs’ can be downloaded from the Sikh Federation (UK) website.