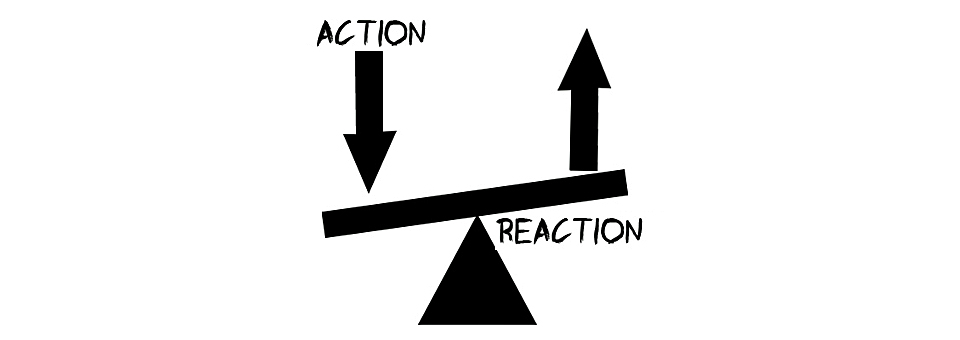

Every action has a reaction. In the context of 21st century society, and for Sikhs in particular spread across the globe and without a State of their own as afforded to other nationalities, is it better to be an actor or a reactor?

When the British Government announced last year that a statue of Mohandas Gandhi would be erected in Parliament Square, there was jubilation amongst some of the UK’s Indian community, but notably there was derision from the UK’s Sikh and Punjabi communities. Since the Indian State came into being, minority groups have questioned whether Mohandas Gandhi deserves to be called ‘father of the nation’, citing his derogatory comments about people of ‘lower’ castes, his unpublicised, mutually-beneficial relationship with the Imperialist British, and the perceived impact (or lack thereof) of his grandiose public statements. It should come as no surprise that amongst Punjabis and Sikhs – who led from the front to rid Punjab of the British invaders – there would be opposition to a Gandhi statue in the most important place in the United Kingdom. That the statue should be opposed is not in question, but what is are the resources that we as a community devote to such. There already exists a statue of Gandhi in central London, in the heart of Tavistock Square, as well as busts which are housed in a number of institutions, some of whom have named rooms and even buildings after him. The new statue would of course attract much greater attention installed outside Parliament, but to an extent there is very little difference, certainly not enough to command a re-allocation of considerable resources to oppose it.

My own personal response has been to write to my parliamentary representative highlighting why the statue should not be erected, bringing to attention scholarly work that has re-analysed just who Mohandas Gandhi really was. As the building of the statue progresses, I will write a further letter addressed to appropriate Government ministers and make clear the opposition of myself and the wider Sikh community. But that is all that I can and will devote to this issue. At any given time I am working devotedly on a handful of projects, and contributing on up to a dozen more. When I react to an event or happening beyond writing about it, I not only divert my time, energy and resources towards it, but also my focus. This can be a dangerous practice because it prevents me from reaching whatever goals had been set for existing projects that I was already working on.

It is I would argue, quite difficult for any individual in the Sikh community to work on well thought-out and planned projects and still apportion time to react to unforeseen happenings with any real impact. We lack the infrastructure and political maturity that is required to cover so much ground. Ours is a small community, but one that has the ability to reach far beyond its means when we dedicate ourselves towards particular goals. Accordingly, many Sikhs ask the question as to why we have in the Diaspora been unable to create productive institutions or organise ourselves on a national and even international basis with influence and legacy; I would point to this reactive nature as a major factor. The Sikh community faces umpteen challenges every day instigated by all manner of sources, from racist attacks based on our outwardly appearance to subversion of Sikh practices in Sikhdom’s epicentre. And on most occasions what we find is a reaction from Sikhs that is disproportionate to when acting of our own volition in a direction that we have planned and agreed upon.

Take for example the call by some Sikh groups for greater police protection in the wake of a cowardly racist attack on a Sikh man in Wales a few weeks ago. Not only was this reaction ideologically out of line with Sikh thought, but it will have an effect on future dialogue with the State that presents Sikhs as Sant-Sipahis and unflinching in the face of oppression of all forms. In a different light but reflecting the same issue, this week Bollywood actor Amitabh Bachchan is appearing on the tax-payer-funded BBC Asian Network; Bachchan has been cited for his role in instigating mobs who targeted, murdered and displaced Sikhs following the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1984. Aside from writing to the BBC Trust and tweeting the unwitting interviewer who happens to be from a Sikh and Punjabi background, reacting to this situation in any other way would draw people, money and valuable time away from their role in existing human rights campaigns – something that few charities and activists can afford to do.

I am not suggesting that the Sikh community should not respond when challenged to do so, but it is my contention that we will not advance until such a time that we work focused entirely on our own agenda. We have not faced a challenge that warrants a deviation of our direction since the invasion of the Darbar Sahib in 1984 (itself an event that was so immense it determined new elements be added to the Sikh agenda) and as such I am loathed to lose focus on where we should be headed. At present far too many Sikh activists and organisations operate to an agenda not of our making, driven by other nations, bodies and even individuals. Until we realise that our priority must be to act than to react, it is unlikely that any actions we take will bear fruit.