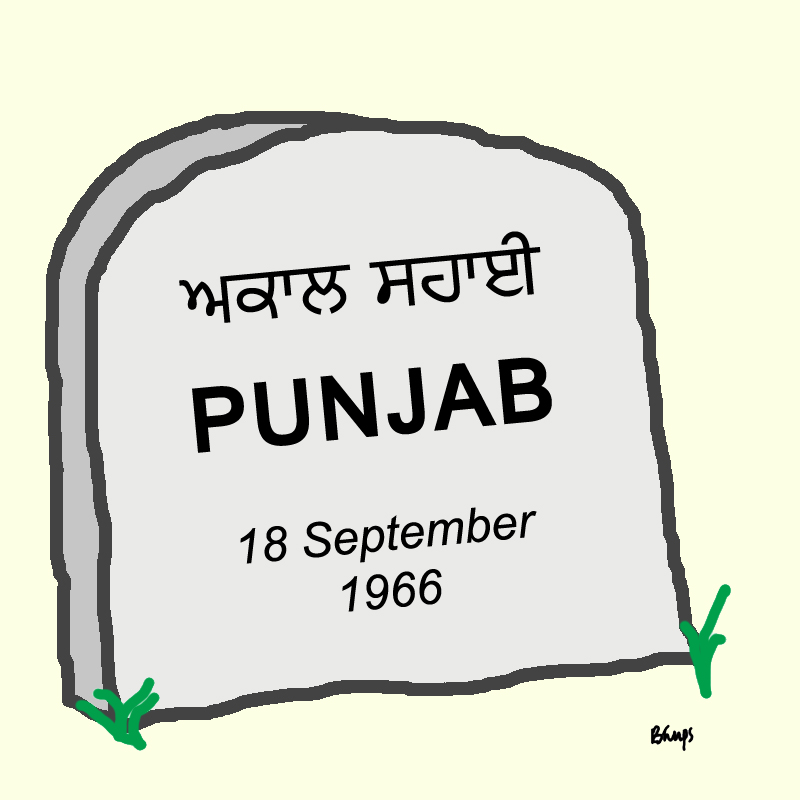

Yesterday marked fifty years since the day that the Indian Parliament passed the Punjab Reorganisation Act. It was on 18 September, 1966, that this death knell for the Punjab was sounded, but it should not have come as any surprise for the fatal shot had been fired before the British ever departed. On a personal level I find commemorating or celebrating days of importance on their anniversary futile, opting instead to remind myself of the symbolic importance of certain days to my life journey at much more emotionally relevant intervals. But recognising that most of the Punjabi and Sikh World do hold importance to these anniversaries, I was disappointed to find that this notorious date on the Punjabi and Sikh calendar went unmentioned, to my knowledge anywhere; perhaps because few know anything of it?

The Punjab Reorganisation Act designated that large numbers of traditionally Punjabi speaking villages, towns and cities, be moved into other states, namely Himachal Pardesh and the newly formed State of Haryana. Whilst this took place with the collusion of some of the citizens of those places (who continue to speak Punjabi informally to this day) it forced a sizeable minority of people into adopting an identity and language that was not their own. Not only was the geographical element of this decision at odds with how boundary changes were being made elsewhere in the subcontinent, but it was another blow at the way in which Punjab, and particularly Sikh citizens, were being treated in the new Indian ‘democracy’. Most crucially though, the Punjab was left without a capital to call its own, as the city of Chandigarh now fell under what is known as Union Territory (central Government controlled) and was determined as a shared capital for both the Punjab and Haryana. This particular consequence of the Act has devastated the Punjab for a number of reasons, perhaps most unnoticeably as a strike at the Punjabi identity.

More specifically, the Punjab Reorganisation Act resulted in decisions pertaining to re-distribution of river waters, construction of energy-producing dams, and administration of electricity, all which moved under the direct control of the State based in Delhi. Arguably this is the most important factor that has led to the devastation of Punjab’s agricultural economy and environment, and was at the heart of the struggle that emerged in the next decade for enactment of the Anandpur Sahib Resolution. Both that movement and the Dharam Yudh morcha were directly concerned in written word and sentiment with the consequences that had resulted from the enactment of the Punjab Reorganisation Act. It is a travesty that this whole chapter of recent history has been relegated to academic circles; whether Sikh or not, every Punjabi has been negatively impacted by the Act and should be fully aware of it. Perhaps the social media debates over Sikh Statehood would then take on a different tone. At the very least, there would then be others who like me would find it ironic that today’s Sikhs are commonly accused as communalist or separatist in nature, and coloured as unable to survive, let alone thrive, in a State that they might call their own, when a State developed under the Arya Samaj banner of ‘Hindu, Hindi, Hindustan’ has risen to the international stage through the annihilation of minorities and whose elite statesmen have repeatedly shown themselves to be dictatorial and self-serving over half a century.

The revered academic, Professor Kapur Singh, who was then an elected Parliamentarian of the Shiromani Akali Dal political party, delivered a speech in opposition to the Bill a fortnight before its passing when it was still being debated in the Indian Parliament. He provided a thoroughly detailed backdrop to how this point had been reached and aptly depicted the Bill as a “rotten egg“. In hindsight it is easier to see why his words fell on deaf ears: this was an establishment set on a course of redefining Indian identity no matter what the cost, as was painfully seen by the invasion of the Darbar Sahib less than twenty years later. The speech was re-published in the book, ‘Sachi Sakhi’, authored by the ‘National Professor of Sikhism’ – a book which should be mandatory reading for every Sikh, Punjabi, or individual with an interest in the Punjab (the speech itself can be found in its entirety reproduced here at the Sikh Siyasat website).

Amongst the everyday Sikh sangat both in the Punjab and abroad, attention is given to the ‘enemy within’ at every stage of 20th century current affairs. This has to stop. The prelude to the Act and the years of protest in support of Punjabi Suba may have been riddled with divide-and-conquer politics played out at the highest levels in Sikhdom, but so little is widely understood and discussed on this topic that we are sticking ourselves in the proverbial mud. The overly-simplified blame is laid at the feed of Master Tara Singh, a one-time head of the Shiromani Akali Dal, but all that accusation proves is how successfully we were divided and conquered. It is of the greatest frustration to me that Sikhs and Punjabis in the West, young and old, who have a wealth of knowledge and experience at our fingertips, are failing to re-examine this chapter of our recent past. It is only natural that following the invasion of the Darbar Sahib, the Diaspora would focus on the brutal annihilation that was then – and to this day is – being perpetrated against the people of the subcontinent. But until we know where it is we have come from, until we can see the bigger picture, there will be something missing inside us and an ignorance impeding our advancement.

In the years that followed the invasion of the Darbar Sahib, Sikhs were left under no illusion about what was taking place; that frustration of having engaged with the political process for decades and then still being coloured as separatists despite being on the receiving end of near-annihilation, was captured in the thought-provoking words of these verses by the UK’s Balhar Singh Randhawa in 1986. In this new series on naujawani, we explore how poetry and music told the story of the post-1984 period, and how Sikhs regained their dignity.