The infamous Koh-i-Noor diamond has been making news headlines once again in recent days. Fuel for column inches has come through a statement to the Supreme Court by the Indian Government’s Solicitor General, Ranjit Kumar, in which he stated that the “Koh-i-noor cannot said to be forcibly taken or stolen as it was given by the successors of Maharaja Ranjit Singh to the East India company in 1849 as compensation for helping them in the Sikh wars.”

Exactly how the Koh-i-Noor came into the ownership of the British Royals following the demise of The Punjab kingdom has been eloquently detailed by a University postgraduate student from the UK, Priya Atwal for The Tribune newspaper. Hers is one of the better opinion pieces highlighting the obvious – that the fallen sovereign of the Lahore Darbar, Maharaja Duleep Singh (himself not even in his teens) had no option but to accede the treasury and his throne to the victorious British; knowing this, everybody is asking, why has the Solicitor General stated that the Koh-i-Noor was “given” to the British?

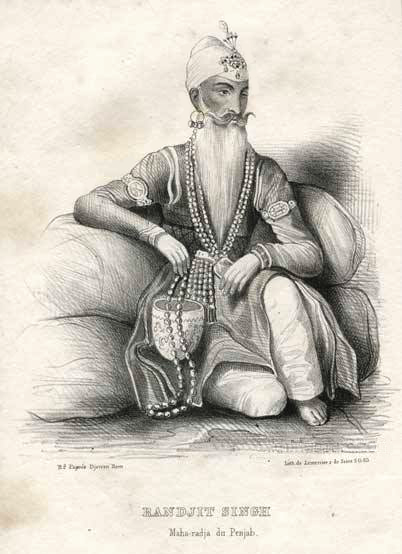

When the Punjab was annexed in 1849, a mere ten years had passed since the death of Duleep’s father, the Sher-e-Punjab Maharaja Ranjit Singh. It is understandably a sensitive issue even today that the Lahore Darbar, the Punjab and the Sarkar-e-Khalsa were then a defeated entity. Irrespective of the duress that Duleep was placed under however, there should be no misunderstanding – the Koh-i-Noor was given to the British; it was no more stolen by them than when Maharaja Ranjit Singh himself acquired it from Shah Shuja. To the victor go the spoils, and when the Punjab was lost for so many differing reasons, those who remained standing took control and possession of what they willed, including the Koh-i-Noor diamond.

I find it remarkable that so many Sikhs in particular have taken their time to jump in on this issue through social media and the like. With so much else going on in the Punjab and elsewhere in the Panth that hardly gets noticed, why is this becoming a discussion point for everyday Sikhs? Maybe because on the face of it this is an easy topic to form an opinion on, one that requires little comprehension of history or the socio-political nature of our lot today – the British took our “Raj”, our land and our wealth, all three of which are embodied by the Koh-i-Noor, to which a claim of restitution at least appeases our own conflicting feelings when it comes to statehood. But we would be wrong to so nonchalantly deem this issue as a no-brainer and in fact, if we consider this issue in greater depth there is something of an epiphany to be had. That deeper analysis can start with the words of the statement that have sparked this latest coverage. Accordingly, it is after much ponderance that I say the Solicitor General was not incorrect; he was perhaps incomplete, or even misleading, but no more. I believe that Kumar intentionally ommitted to make it clear that this was an act of giving enforced upon the last Maharaja of the Punjab in his statement to the Supreme Court, for a number of reasons.

Firstly, if the Government of India, represented in this instant by the Solicitor General were to openly state that the Koh-i-Noor was stolen from the Punjab Kingdom, where does that leave the interpretation of their own actions since the Indian State came into being almost seventy years ago? In that time, entire villages have been demarcated from the East Punjab, river waters have been redirected to other states, and the border with West Punjab has denigrated into a war zone so that the two siblings Amritsar and Lahore have been forced to grow within glimpse of one another but forcibly kept apart. If the Koh-i-Noor – a jewel with a finite value albeit one of immense proportions – is deemed to have been taken or stolen by the previous all-conquering rulers from London, what does that say about the resources that have been usurped since 1947 by the recent all-conquering rulers from Delhi?

Secondly, the Koh-i-Noor like so many other treasures belonging to any State, is a symbol of power; whosoever is in possession of them, exerts an unequivocal authority over that State. For the present Indian Government to be associated with a treasure that they openly admit to having been historically taken from the lands they administer, is a sign of weakness. It detracts from the show of complete power and domination that has become synonymous with the Modi-led Government. So rather than say that the Koh-i-Noor was taken by the British it is easier to adopt the more amicable line that it was given to them, and notably that by the Punjabis (read here Sikhs) – not the Indians.

Thirdly, there is a broader positive here for India’s ruling elite, including Punjabi-Sikh political entities Akali Dal Badal and the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhik Committee (SGPC) both of who are in election campaigning mode. Badal Dal has used the opportunity to stake SGPC claims of ownership on behalf of the Sikh community whilst the SGPC themselves have been able to echo the simple thoughts that pervaded social media in an ongoing attempt to redress the notion that they are out-of-touch with common Sikhs. The real conversation that should have been taking place alongside this one is that of a future restitution of pre-partition Punjab, or even a pre-1966 Punjab, both of which the Akali Dal in all its derivatives is mandated to .

Time after time the issue of the Koh-i-Noor resurfaces, with everybody from India to Pakistan via the Netherlands, exerting ownership rights. As Sikhs in the Diaspora with access to information, knowledge and insights not readily available in the sub-continent, we have a responsibility to delve deeper into issues such as this to determine what is really being said. We need to learn how to carry the conversation forward so that it is beneficial and not mere click-bait content for the online aggregators to fill your screen with more advertisements. The Indian Government has clarified in a statement that they are committed to “make all possible efforts to bring back the Kohinoor diamond in an amicable manner.” Then what if Punjab were to advocate a redraft of it’s borders to their pre-1966 positions or similarly the restitution of it’s river waters in an amicable manner? Or – as is stated in the Ardas made by Sikhs every day – to unify the two historically relevant Punjabs, in an amicable manner?