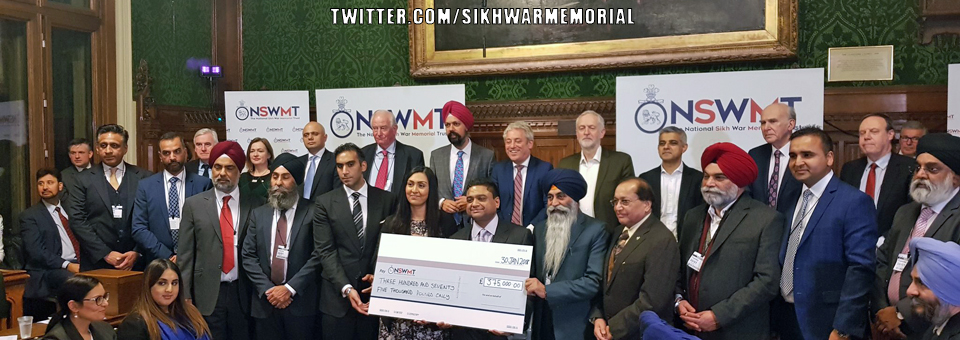

Last week a campaign for a National Sikh War Memorial was launched at the Houses of Parliament in London. Led by the first-turbaned MP in the UK Tan Dhesi, the campaign calls on the Government to actively support the erection of a permanent national monument in a prime central London location. The launch event in Parliament attracted high-profile politicians including the Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, London Mayor Sadiq Khan, Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow, Communities Secretary Sajid Javid, and Liberal Democrats party leader Sir Vince Cable. The event had the desired effect and it was announced that the campaign had received Government backing; steps will now be taken to find a suitable location. Naturally the story has prompted coverage in the national and regional press, as well as in the sub-continent, appended with photographs from the event in Parliament. It is at times like this that difficult questions tend to go unanswered – or more frequently, ignored altogether; with that in mind I find myself asking, do we really want a statue for Sikh soldiers?

Before you read on, I need to clarify the purpose of this article: it does not concern whether we (Sikhs) really want a statue for Sikh soldiers [note: I feel dirty for the clickbait-esque heading, sorry] but undeniably this subject matter does have a significant part to play in prompting a more pertinent question: how do Sikhs decide what they want (and don’t want) at a national level in host countries?

On the face of it, the call for a statue memoralising the contribution of Sikh soldiers during the World Wars is a positively uncontroversial one. It’s the kind of feel-good story that the press and politicians love, showcasing their ability to engage and work with a minority, non-white community. For the Sikh community’s part, it provides much-wanted media attention, as well as public recognition of the sacrifices that were made by our predecessors in fighting oppression. Why would anybody possibly oppose this?

Whilst it is difficult for a Sikh to dispute the respect accorded to any person who has given their life fighting on a battlefield, it does not follow that their intentions or the circumstances in which they felt compelled to do so are beyond question. Were Sikhs who left their homes to fight and die in foreign territories across both World Wars doing so out of a sense of duty to free the World of tyranny, or because their conquering masters from London ordered them to do so? Further, it is not disingenuous to raise a question over the ambiguity that pervaded Sikh intelligentsia at the time, aiding the lure of joining the Armed Forces of the British Empire for the Punjabi native, particularly the Sikh. With question marks over what Sikh identity meant in the early Twentieth Century, one shouldn’t begrudge those who joined up, but that does not preclude us considering that these were the same Sikh people whose blood was shed at Jallianwala Bagh and Nankana Sahib following the end of World War I, and who were left utterly destitute by the creation of Pakistan and India following World War II. Is a statue that symbolises this era of confusion and political poverty appropriate, and that in the heart of the Empire under who we suffered so greatly?

Perhaps the idea of this statue is not as straight-forward as first thought. But this brings me to my real question: where are our fora to deeply consider, debate upon, and then present to the Panth, the appropriateness of initiatives such as a statue for Sikh soldiers who fought in both World Wars? We have umpteen organisations, charities and bodies, even a few leading groups (Sikh Council UK, Sikh Federation UK, Network of Sikh Organisations) that speak on our behalf – but we have almost no think-tanks or fora to leaven our intellectual reasoning and provide much-needed direction. And this is an ever growing problem for us not only outside Punjab, but within it too. There are few platforms and spaces for open dialogue, free of intimidation, rhetoric or infiltration. We are not entirely bereft of these institutions (I would like to think naujawani provides some level of deep-thinking on topics of importance to Sikhs) but we have nowhere near the quantity and quality needed for us to climb out of the situation we are in.

Let’s fast forward a decade from now; the statue is in place and during a political protest an individual defaces the statue because of what it symbolises, as happened in 2015. How do we feel now? Do we oppose the protestors clamouring for increased rights and an end to austere measures taxing the most needy, or do the Sikhs of Guru Nanak themselves reflect on whether the statue was a good idea in the first place? This is the type of thinking we need to invest in right now; alas you or I would be lucky to scrape together one percent of what has already been raised in private donations to build the statue (£375,000 if you’re wondering).

I’m not for or against the memorial statue, despite what you might have read on this page. But I am opposed to doing things without thinking them through thoroughly. And I’d like to put the question to the Sikh World as to what we want to do about that.