The recent parole release of Sikh political prisoner Professor Devinder Pal Singh Bhullar in Punjab has been greeted with satisfaction by the global Sikh community and human right activists alike. A two decade long campaign against the wrongful sentence and incarceration of the one-time Professor of Engineering from Guru Nanak Dev Engineering College, Ludhiana, has at long last begun to bear fruit. The decision to release him on parole is of course to be welcomed and one hopes that for the first time in so many years he is able to see his family and friends with a sense of freedom. But in the greater scheme of things, I argue that this occasion is neither a victory, nor a sign that times are getting better, and it may in fact point to quite the opposite.

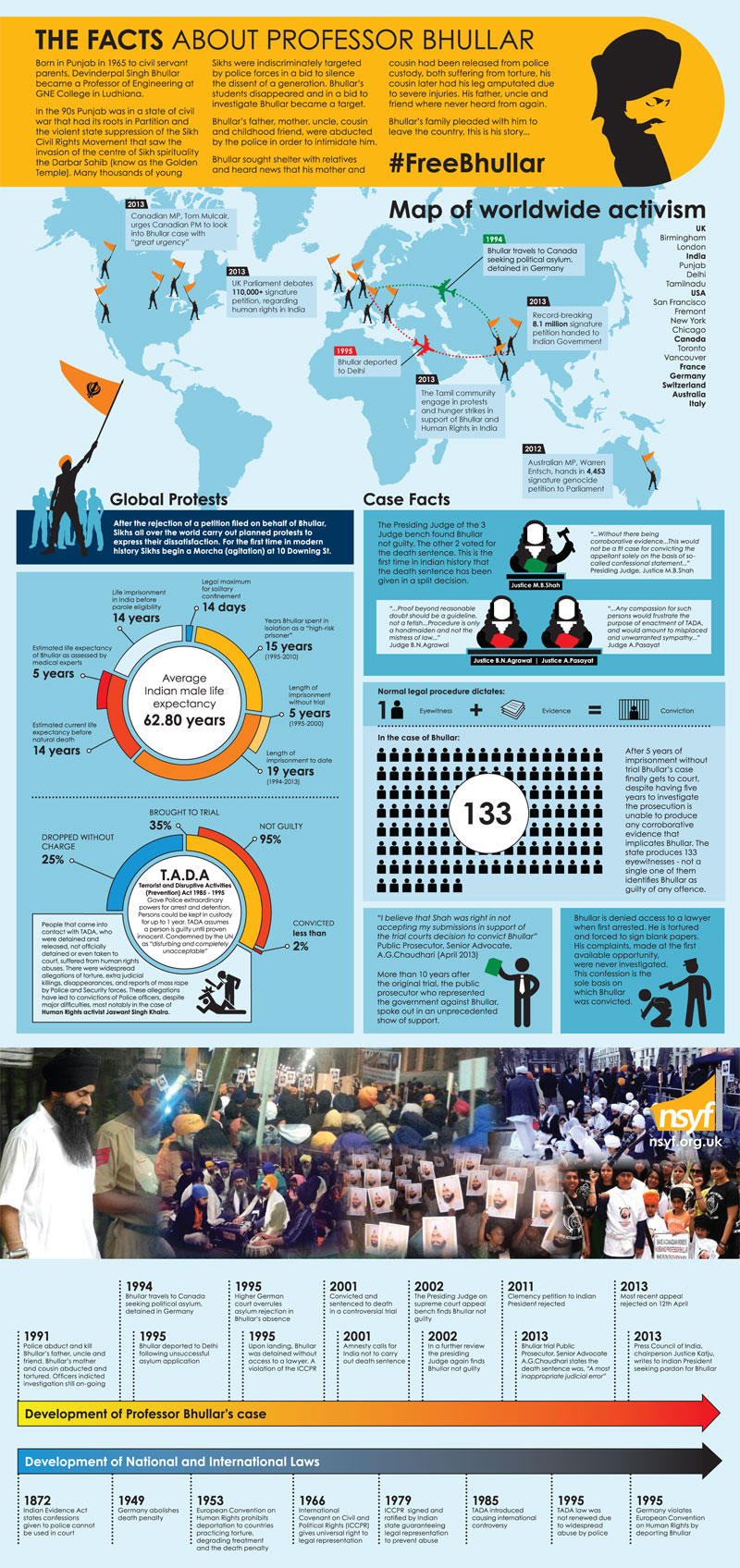

Professor Devinder Pal Singh Bhullar was released on parole for 21 days late in the evening on Saturday 23 April. He was met by his wife Navneet Kaur and briefly addressing members of the press simply uttered, “Sabh da Dhanwaadh” meaning “thank you to all”. There have been so many twists and turns in this story that one can find a timeline of what took place within archives on most news-worthy sites including our own. In the last year, Professor Bhullar had been moved to Amritsar from the notorious Tihar jail and was recently moved into a Government hospital in the city, reportedly in poor mental health. Most readers will recall that in April of 2013 his death sentence was upheld by the Supreme Court on a technicality, leading to worldwide outrage amongst human rights observers, fellow academics and minorities groups. It was Sikhs in the Diaspora however, who were the most vocal in the campaign to clear Professor Bhullar’s name and those efforts were at least successful in taking the campaign to a global scale. Co-ordination between activist groups stretching from South-East Asia to North America might not have been perfect, but it was as organised as it had been for thirty years and the professional attitude adopted by an educated generation born outside of Punjab was typified by this infographic from the NSYF (reproduced below) which was widely shared, printed and distributed across the globe. Although those efforts may have contributed to the commutation of the death sentence to life imprisonment in March of 2014, they paled in significance to the influence of power brokers in Delhi who ultimately wield the decisions of the Indian State.

It is here and now where Sikhs need to use foresight, taking into account how events have unfolded in the last hundred years and more on the sub-continent, and what might be the meaning behind the decision to provide parole to Bhullar as well as another prisoner Gurdeep Singh Khera a day earlier. Public Sikh discourse needs to move beyond the obvious questions asking whether these are one-off occasions for parole or will be repeated; whether permanent release could be achieved; and perhaps even if exoneration might follow (although asking these questions at all would be a good start in some spaces). There are more important questions that should be addressed and debated as to whether release from incarceration for the individual is even true freedom at all. Once “free”, are they permitted to move freely or as has been repeatedly experienced to my knowledge, are political prisoners’ movements and activities curtailed indefinitely still?

Much of the general langar hall and social media conversation touches on these questions in the most banal way, pointing out the impending State elections next year that might be pressurising the ruling Akali Dal (Badal) to appease Sikh sentiments and activate parole releases. For sure, elections are due next year whilst SGPC elections take place this year, but presuming that this applies pressure on the all-powerful ruling class of Punjab, not to mention their counterparts elsewhere in India, is evident that we as a collective are not yet awakened to the character of the foe that dictates our time. This was similarly exemplified when countless Sikh media sites and commentators lauded the UK-based Sikh Human Rights Group’s statement to the Hindustan Times newspaper inferring ‘conversations’ with the Modi-Government to have been responsible for impending release of prisoners including Professor Bhullar, which is not what the paper said at all as I debunked at that time. What needs to be clear is that political prisoners of any minority are released in India when, and only when, it suits the purposes of the State. It is a decision that will have been taken months if not years in advance and will form part of a larger policy decision based on the state of the nation, the movement, and Sikhs themselves.

And this leads us to the questions that I believe should be asked more publicly within Sikhdom, even if their debate is limited to Sikh intelligentsia. Professor Devinder Pal Singh Bhullar’s case was an example of the story that has gone untold of the freedom movement in Punjab, one that belonged to thousands of academics; graduates, post-graduates, researchers and faculty whose lives were destroyed because of the way they thought. Professor Bhullar was innocent of all charges made against him; he was targeted by the State in such a heinous way because he was a bigger threat than any separatist who leaves home carrying a firearm or an explosive device – he had the ability to think. Where we stand today in the Diaspora, we have access to resources, content and power that the Punjabi freedom fighters of the 1980s could never even dream of, but because our thinking has been controlled through propaganda and our mind-states have been altered by an unquiet storm that continues to go unnoticed, although we have the capacity to think like Professor Bhullar, we do not. His was a case that should never have reached this point and his parole is to be welcomed from both a personal point of view for a man whose life has been destroyed, and collectively for us as a Panth. But it is little victory – nay, it is no victory; if anything, our belief that it is suggests that perhaps we have already lost.