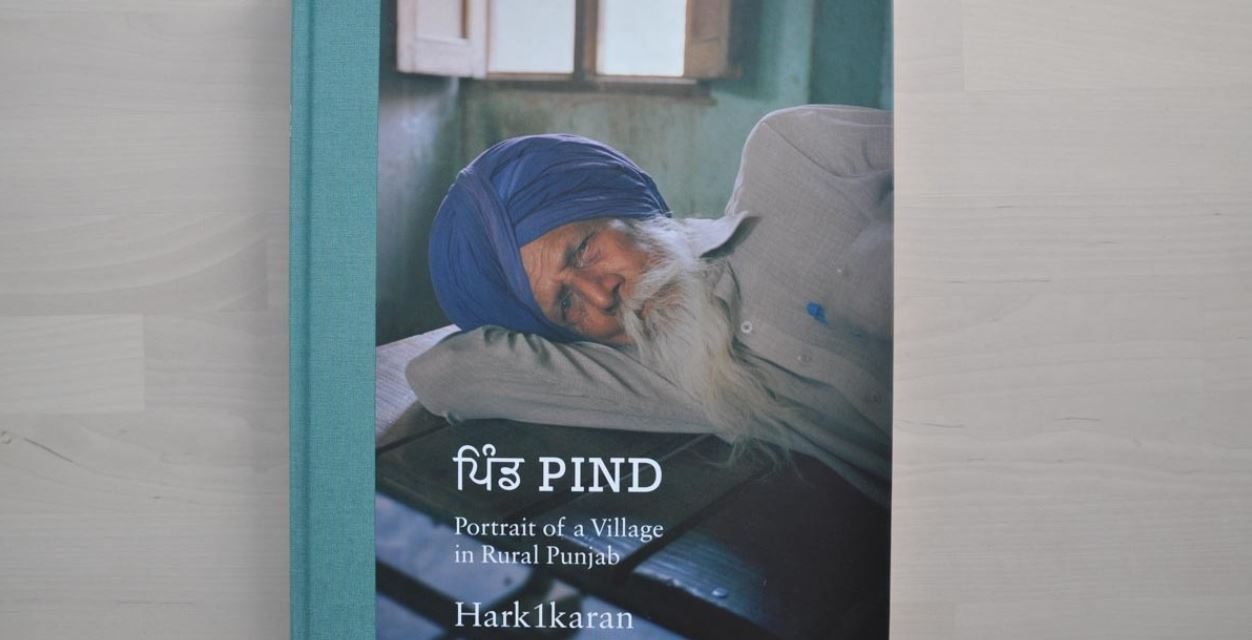

‘ਪਿੰਡ PIND’ is a photobook self-published by Harkaran Singh Gill, a UK-based photographer known better by the creative moniker ‘Hark1karan’. Released this summer, the work portrays Punjabi village life as seen through the eyes of the photographer from March 2017 to May 2018. The published work is an exciting release, not often seen in both subject matter or presentation, and is one that I have spent considerable time perusing in lockdown-London. Photography is not a medium that I am used to, particularly when it comes to a review, but I was intrigued to know if ‘ਪਿੰਡ PIND’ lived up to the promotional blurb which depicts it as ‘for those seeking home’.

First I must declare that I have met the photographer a handful of times, originating with when he shot photography at a bhangra competition I was organising five years ago. Although this book was sent to me without fee, as with all of our reviewed material it has since been purchased at full price in order to proffer an objective review. And let me say that buying wasn’t a difficult decision to make on the basis of the quality of the product alone – this is an impeccably produced hardbound publication that feels every bit as authentic as the subject matter of the photographs – of which there are 130 images across 192 pages. Priced at £35 (discounts are available periodically) I don’t think it unfair to say that this book will not be landing on every Punjabi’s coffee table – but perhaps that is a good thing because this is no mere coffee-table paperweight of a photobook; it deserves a much more valuable place for the thinking ‘reader’.

Hark1karan shoots on 35mm film and that decision was complimented by a print reproduction in the book that adds to the feel of the pages as you turn, allowing the lingering on individual images to be a pleasant experience. Shot intermittently in three different seasons at the photographers maternal village of Bir Kalan, the photos don’t so much leap out of the page as much as they embed themselves into your process of digesting. Occasionally thought-provoking, genuinely intriguing and always instigating conversation with those of us fortunate enough to have wider family whom have lived in the Punjab, the photos depict everyday life in action as it really transpires – his timing and positioning show what is real, rather than something concocted. The images vary considerably, but are always informative; subjects are captured respectfully and insightfully, revealing the person behind the face with sensitivity. Equal respect is given to landscapes where even the most starkest of subjects go unimposed on the viewer – the image of the village ‘Hadda Rorri’ exemplifies this as the carcasses of cattle are less shocking and more telling of the cyclical nature of life inherently appreciated by the rural communities of Punjab.

Hark1karan makes no secret of the specific nature of this work, shot entirely in a single village in the Malwa. Had this been a village in the Majha, or in my homeland of the Doaba, I can envisage the photographer depicting the reduced open space and physical differences of the people just as aptly. In his introductory chapter, Hark1karan moots that his repeated visits over three decades helped build up the context to this work as well as his capacity to communicate with the people of the village. However, such skills are not limited just to this work and a cursory glance over the photographer’s Instagram page prove such. His attempt not to romanticise the lifestyle of Punjab is achieved, and moreover, this work will instigate more learning than perhaps he had hoped and aimed for.

I found something quite humbling in ‘ਪਿੰਡ PIND’ epitomised by the photographer’s recognition of his privilege at having had the opportunity to experience the ‘motherland’ so many times throughout his life (three decades). Many of us who are of Punjabi-origin visit irregularly, if at all, and in a blur at that, constantly visiting historic places and extended family. That humility comes through in the selection of photographs – this book is for those seeking home. Is it your home? That is irrelevant. It may be home for the photographer in his living and/or generational memory, but to the viewer it shows a world that is home for all of us – one where the people and places we recognise from the stories told to us as children are alive and breathing. To me it enhanced a conversation I’ve been engaged in for many years asking just what is home, what happens to the characters and narratives of that home when I am not there, what is my relation to that ‘home’ when I reside elsewhere… no mean feat for a picturebook.

‘ਪਿੰਡ PIND: Portrait of a village in Rural Punjab’ by Hak1karan is available to buy now online at https://www.hark1karan.com/shop/.