‘Morality in War and Peace: Perspectives on the Zafarnama’

Tuesday 18th October, British Library – A Review

Events on the Dasam Granth always cause a stir. Authenticity, controversy, fact and fiction, are all nouns synonymous to the discourse on this great volume. So having been invited to a ‘discussion’ between two eminent authors on a particular element of the Dasam Granth, I really didn’t know what to expect.

My fertile mind pictured on one hand handbags at ten paces, whilst the other, a docile rendition of verb conjugation in Persian. The subject, that miniscule portion of the Dasam Granth that is so central to Sikh morality and ethics, was to be the Zafarnama. Discussing it, at the behest of the Anglo Sikh Heritage Trail (ASHT) would be Professor Christopher Shackle and Navtej S Sarna, both authors on Sikhism and the Zafarnama.

Shackle, for me, has produced the most concise, beautifully apt description of Sikhism in his book ‘Teachings of the Sikh Gurus’, co authored with Arvind Pal Singh Mandair. I fervently read its introduction in those moments of rare introspection among life’s hustle and bustle, and as such owe it much.

Contrastingly, Sarna was unknown to me. Currently the Indian Ambassador to Israel, it was learned that at his wife’s behest his new book ‘Zafarnama’ was written. His father also wrote on this subject.

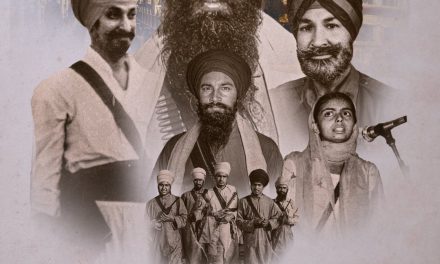

The conversation began with Dr Jeevan Deol introducing the Zafarnama and chairing the conversation. He explained that the use of Persian for the dialogue between Aurangzeb and Guru Gobind Singh was in itself a symbol of the educated nature of the piece. Persian, the language of the kingly court, is used throughout the 111 verses, to convey among a variety of things; the praise of God, the battle of Chamkaur, oath breaking, just rule and reconciliation.

Quite interestingly, Shackle conveyed the idea that the Zafarnama was designed to be read aloud, in front of Aurangzeb and his courtiers. This conjured images of a shocked ruler listening, in the presencet of his nobles, to the words of a seemingly impudent wretch talking of defeat as victory, and saying that his oaths are not worthy, and that his tyranny will come to an end.

Central to Sikh psyche is verse 22 (Chun kar az hameh…). It underpins much of what could be described as Sikh ‘Just War’ theory, and defines the boundaries and tolerances that Sikhs are held to. In its raw Persian form, as Dr. Deol conveyed to us, it can be read in many ways. Apparently, due to a ‘vowel switch’ in Persian, it now sounds different to what it would have in the time of the Gurus. I should be forgiven for slightly switching off at this time. Linguistics interests me, but not being a Persian speaker, much of what was said by Dr. Deol lost on me.

However, what did pique my interest was the rather flattering idea that Guru Gobind Singh had quoted famous Persian epics and poets in this piece. Often Sikhs are portrayed as a hairy uneducated bunch, but here, if what we are led to believe is true, Guru Gobind Singh uses familiar, contemporary (although contemporary with the noble elite) excerpts from Sheikh Saadi’s Gulistan, and more overtly the writings of the poet Ferdowsi. The idea of the Guru quoting Sheikh Saadi in verse 22 leads me to surmise that he wanted to impress upon Aurangzeb that even a renowned poet and co-religionist of Aurangzeb justified taking to sword if all other means failed.

Now, amongst all this post mortem of the Zafarnama, I waited to hear actual excerpts of Sarna’s translation. And what a piece it was! The tempo and rhyme was perfect. Added to this was the aura created by Sarna’s Indian-English accent and soft tone of voice. Contrastingly, Shackle’s translation was ‘more correct’, but the absence of rhyme and less flattering language took away much of the drama and spectacle that Sarna’s created. Yet in truth, they were both pieces describing the same events, and the choice of adjectives each had chosen really did not deviate towards controversy.

In ending, I surmise that what the authors have produced are two different ways of examining the Zafaranama through English as a medium. On one hand we have artistry and flamboyancy, much like the original would have been, and on the other a concise translation with linguistic correctness at its fore. Both are definitely worth a look at, and deserving of a place in any Sikh enthusiast’s library.