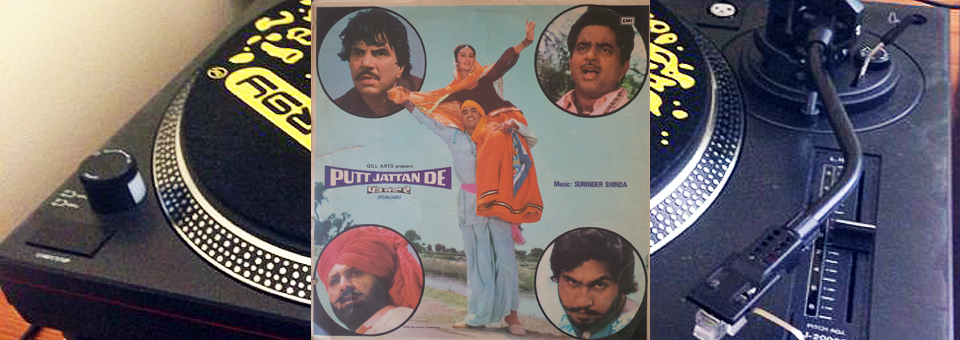

I love punjabi folk music. Growing up, I would watch my dad carefully removing vinyl records from their sleeves and placing them lovingly onto his Hitachi record player. As I got older, I was allowed to start using the cassette deck, but not the vinyl and I didn’t understand why until the day I snuck into the ‘nice sitting room’ reserved for visitors to our house, took out a record and played it on the turntable. I danced around the room, arms in the air and screeching the chorus line at the top of my voice. When the track ended I leapt over and dragged the needle back to the edge of the vinyl as I had seen my dad do umpteen times… except I had barely lifted the stylus from the deck. Despite leaving a permanent scratch on what was once a mint-condition vinyl album from the 1982 motion picture ‘Putt Jattan De’ my father let me inherit his record collection some time ago and although it has never been played since, that album remains one of my most prized possessions.

Naturally, when I came to hear that my favourite Punjabi producer Tru Skool was revisiting the title track ‘Putt Jattan De‘ for an upcoming release, I was intrigued if pessimistic. It is always difficult for musicians to tackle a classic song, but this is not just any song – it is quite possibly the most recognised Punjabi folk song of all time, alongside ‘GT Road’ – so I was simply hoping for an adequate version that would not sully my feelings for the producer. I needn’t have worried as the highly talented Tru Skool delivered an exceptional work of art. This is a song in its own right that pays homage to the original whilst introducing new ideas and is most pertinently a fitting tribute to the god-father of Punjabi folk music production, Charanjit Ahuja. It may not be to every listeners taste, but for a lover of Punjabi folk music it offers a lifetime of enjoyment.

From time to time I like to use social media and my position as a writer to share music that i’m enjoying, particularly music that is different to the status quo. This track fits that bill, but I held off doing so because I didn’t know how some people might react to it. ‘Putt Jattan De’ is perceived by many to be a song promoting the caste system – a hierarchical stratification of people based on their employment and social status. In India a person is deemed to be of a certain caste from birth and despite the rise of the sub-continent as a global power, many are still looked down upon purely because of who they were born to. Sikhs have always rejected the caste system and rightly so the vast majority of people in this day and age have joined us too. However, my own reluctance to share this track made me think twice about whether it did indeed promote a caste system and led to me writing this article – in part my way for promoting the track which is an excellent example of a Punjabi folk music tradition that is rapidly diminishing.

Punjab has long been invaded and inhabited by different groups of people who today make up its population. Over the last five hundred years, the caste system there has widely been rebuked, heralded by the arrival of Guru Nanak who also helped to destroy the divisions between different faiths and genders. This was embedded into the lives of Punjabi people by the establishment of the first Khalsa Republic by Banda Singh Bahadur in 1710 which destroyed the prevailing feudal system. Rural life evolved in the land of the five rivers as one reliant upon people of all trades operating in unison, as is so vividly depicted in literary works such as ‘Mera Pind’ and ‘East of Indus’. My own experiences of Punjab reflected the way we were brought up in the UK by my parents, socialising with familial friends of all manner of backgrounds who shared in the joys and sorrows of our daily lives. Whilst on an extended visit to Punjab, my father went to great lengths to explain to me how the Punjab he had grown up in was a harsh environment which demanded discipline and cooperation. Over the last fifteen years I have travelled to our familial village with him a number of times and seen him embrace old school friends, farm labourers and village elders of all ‘castes’ as tightly as he would his own children. I learnt that the caste system in rural Punjab did not exist as we might think until the latter half of the twentieth century when the Green Revolution took hold of the State and emaciated the land, bringing short-term benefits for some and not others, but ultimately destroying the place for everyone. People may have lived in a somewhat rigid manner, but none acted as if they were able to rule over others and this included the farming tribes of the jatts, sainis and jagirdhaars.

This brings us back to the song itself and whether it promotes a caste system. Even a cursory look at the lyrics reveals four verses depicting young jatt men as being brave, fashionable and unflinching in doing the right thing. Does this suggest that only they (jatt young men) behave in this way, or moreover that all of them share these personality traits? Of course not! So why produce a record mentioning jatts in this way? Leaving aside the artistic licence which all musicians have the right to use, this song and many others like it lauding the achievements of jatts come from the way in which they as a tribe were perceived in their rural communities. They were a product of their environment in which they were seen as combative members of the community who could be relied upon in times of trouble. Whether the same is still true is debatable, but that does explain the origin of such lyrics. On that basis I would argue that this track doesn’t promote the caste system, any more than Dips Bhamra’s ‘Putt tarkhana de’ does or Kuldip Manak’s ‘Dulla’ does for rajputs.

In writing this article, I have only hoped to show that there is much to debate and discuss on this issue if we are to advance – it is not black and white as might be seen from a prominent radio station in the UK who have toyed with banning any records from airplay which merely contain a word that is associated (rightly or wrongly) with the caste system. It’s food for thought that if the mere mention of the word ‘jatt’ is so unfavourable, are we Sikhs expected to rewrite the instances of its appearance in the Guru Granth Sahib? Twice it is used in reference to the Bhagat Dhanna and once to depict a farmer. Would a musical rendition of such lines from the revered Guru Granth Sahib also be seen to promote the caste system?

Today, there are clear problems of discrimination that exist across the South Asian community across the World and caste is a basis of these, just as race, gender and religion are too. They are issues that require resolution, but that can only come from a deeper thinking and understanding of the way people live. It does nobody any good to think of caste in terms of a black and white problem. As in so many ways as a community, we need to open up and talk about these issues frankly with a real determination to resolve problems and not push personal agendas. Those who use their lineage in any way shape or form to belittle others should always be remonstrated against, but of itself does this record do that? In my opinion it does not.