I went to see a documentary film recently at the British Film Institute in London. The film was called ‘Concerning Violence’ and was based on Frantz Fanon’s essay from his 1961 book ‘The Wretched of the Earth’. The film was narrated by singer-songwriter Lauryn Hill and showcased nine different chapters of the African struggle for liberation from colonial rule during the 1960s and 1970s.

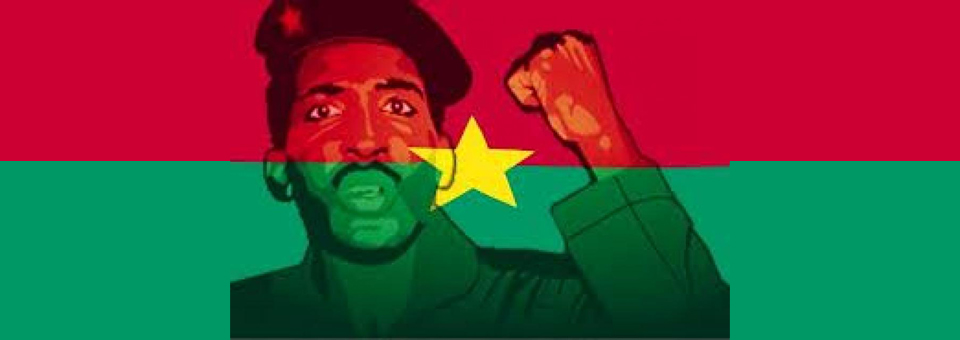

The footage was captured by Swedish filmmakers who had ventured into Africa during the middle of the Cold War to report on the anti-imperialist liberation movements. I was fascinated by the portrayal of the African armed struggle as I had previously known little about the guerrilla soldiers of FRELIMO in Mozambique, or the charismatic General Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso. A revolutionary in every sense of the word, Sankara was responsible for introducing some of the most ground-breaking policies for social and political change Africa had ever seen.

Sankara’s domestic policies were largely focused on the prevention of famine and prioritisation of education. He was also a keen advocate for public health and led the vaccination of approximately 2.5 million children against life threatening illnesses. His foreign policies included nationalising all land and mineral wealth, pushing for debt reduction and minimising the influence of the World Bank. Sankara was bold and decisive during his reign; he retitled the colonial name for his country from ‘Upper Volta’ to Burkina Faso, which means land of the upright man.

In his short interview, Sankara was calm and collected throughout. He spoke about the food aid offered by foreign countries which he had refused to accept. His reasoning for this decision was quite remarkable. Sankara spoke about the need for his country to strive for stability through its own efforts and struggles. In accepting the food aid, he felt that his people would remain enslaved; dependent upon those that once colonized them for their most basic of needs. Instead of food aid he questioned why foreign countries did not offer machinery or others tools that his people could use to create and control their own sustenance.

Sankara showed great foresight with plans to build a road and rail infrastructure, whilst simultaneously identifying the imminent dangers of desertification for which he introduced a program of planting ten million trees. Sankara also championed women’s rights which led him to outlaw female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy. He further encouraged women to work and himself appointed women to high governmental positions.

Although Sankara was a hero for the impoverished people of Burkina Faso, his style of governance alarmed the small but powerful group of Burkinabe middle-class tribal leaders. He was assassinated on 15 October 1987, betrayed by his own associate. Sankara knew that he was risking his life but remained steadfast in his views. A week before his assassination he declared, “while revolutionaries as individuals can be murdered, you cannot kill ideas”.

Whilst watching the documentary I couldn’t help but think about the plight of the Sikhs following the annexation of Punjab in 1849. During the struggle against colonial forces, Sikhs made up 93 of the 121 patriots that were sent to the gallows. They also made up 2147 of the 2626 that were sentenced to imprisonment. A remarkable feat in its own right, especially given that the Sikhs made up just 1.5% of India’s entire population. The Sikhs gave an immense sacrifice and thus spearheaded the movement for independence. Despite their unrivalled sacrifice, it was Mohandas Gandhi et al who took the limelight for securing Independence in 1947. Perhaps more worrying for the people of Punjab was the ramifications of the Radcliffe Line which split Punjab in two. Some argued that this wasn’t an issue, provided the rights of the people of Punjab were safeguarded. However, long after the British ships had set sail, Punjab was the target of further economic, social and religious subjugation. This gave rise to the Punjabi Suba Movement of the 1950s, a long drawn political agitation in which the people of Punjab demanded that Punjabi be recognised as the main language of the State. Later came the Sikh Civil Rights Movement (SCRM) in which the Sikhs worked tirelessly to safeguard the rights of people in Punjab. The SCRM was not resolved through diplomacy as initially intended by the Sikh leaders. The Central Government refused to hold round-table discussions on a number of occasions, choosing instead to respond with violence in hope of demoralising the movement and in anticipation of provoking the Sikhs into a violent frenzy.

However the Sikhs remained steadfast in their movement and chose instead to raise the level of civil disobedience. They planned to hold all shipments of grain from leaving Punjab in hope that it would finally pave the way for a diplomatic resolution. The Central Government responded with heavy artillery and gunfire which served as the catalyst to the armed struggle that followed. Inevitably the declaration for a separate Sikh homeland was made on 26 April 1986. The Sikh Nation passed a Gurmatta and exercised their right for self-determination. This was the outcome following years of non-negotiation from the central Government. All peaceful means of resolving the issues in Punjab had been exhausted. The army invasions of Darbar Sahib left the Sikhs with no other option but to launch an armed struggle against the Government. Much like Sankara, the freedom fighters of Punjab were picked off one by one, and on many occasions it was due to betrayal from within.

The effects of imperialist rule continue to haunt those that were once colonialized. Thomas Sankara realised the importance of setting his people free from mental slavery, and although the Sikh’s struggle post-1947 was not against colonial rule, the Sikh leaders too displayed the same spirit in standing against the injustice that had besieged Punjab. They took up arms because it is the natural progression of fighting injustice. The Guru himself taught the Sikhs this when he adorned two swords in his 6th form. Physical force was and remains a necessary and liberating tool for the oppressed.

In the words of Frantz Fanon, “Imperialism leaves behind germs of rot which we must clinically detect and remove from our land but from our minds as well.” The early Generals of Khalistan removed some of those germs during the Sikh struggle for independence. Despite this, the Sikhs as a whole continue to petition various Governments across the commonwealth for ‘justice’ in search of some form of symbolic relief. They will not find any justice from the heirs of imperialism, for true justice is always taken, never given.