Recently I took the decision to stop using my Facebook profile and all but end my surfing time on the gargantuan social media website. I’ve been using Facebook for over 7 years and although I will continue to log on to ensure our fan pages are regularly updated with posts, photos and videos, I’m moving away from being an ordinary user because of the frustration that Facebook leaves me with; not because of my concerns over how personal information is being mined by advertisers, nor the bias of the news feed, or even the incessant tags I receive in status or photos that have little to do with me. What I’m frustrated by is the growing menace of ‘sheeple’ on Facebook who are emerging at the cost of their reasoning, critical-thinking and individual expression.

Our ability to communicate effectively with our fellow beings is vital to the progress of our society. The way in which we convey our feelings, ideas and questions to one another determine the responses with which we are met and in turn effect the collective advances we are able to make. We happen to be living through a telecommunications revolution where communication between individuals can be constant and is at the very least ever-present. That means that whether it is through social media, online publishing or even the more traditional means of the printed word, the ability to articulate ourselves has never been more important. In this new landscape of virtual interaction, the words we use define the reality that we create for ourselves.

I should have seen this day coming: a few years ago I had a minor spat on Facebook about fellow Sikhs repeatedly using the phrase ‘Rest in Peace’ when talking about a deceased person. On the face of it, most people who comment RIP online do so more out of respect than with any deeper thinking of what the phrase means or represents. But as I tried to reason at the time, these three little words symbolise the assimilation that Sikhs and other South Asian communities in the West suffer from today. Life in the Sikh experience is not limited to this particular existence, despite the emphasis being on maximising the productive experience one has whilst living. To suggest that upon death a person goes on to rest is contrary to the teachings of the House of Guru Nanak. As an alternative, I explained that using the words ‘Akaal Sahai’ were probably more appropriate – defined as, ‘may the Immortal One protect’ – as they better reflect the manner in which Sikhs understand both birth and death. I was met with a little opposition, but mostly disinterest (a sign of the times not alien to me or readers of this article I’m sure). What many Sikh friends did not and still do not understand is that such a simple phrase used regularly has brought us to this point: where today many Sikhs view ‘Sach Khand’ as an equivalent of heaven (it’s not), where life must be ensured at all costs a la Rajoana (against his wishes, denying him the punitary end he had sought and sentencing him to a life languishing in the Indian prison system), and where the value of a couple or adult individual is partly based on the offspring that they bear.

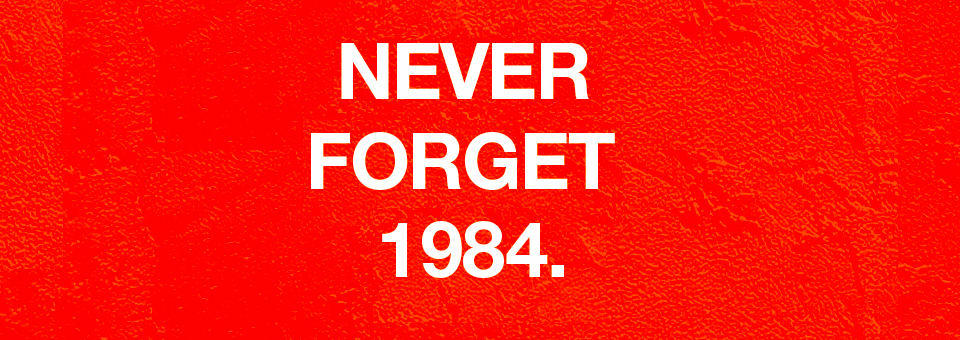

The problem as I see it is with the words that we choose to use and whilst Facebook is not alone in being a medium for communication like this, it has a system that exposes the casual user to cultural misappropriation repeatedly and perpetuates this innocently enough through the simple functions of ‘liking’ and ‘sharing’ content. The most recent incident of this which led me to leave Facebook (partly i’ll admit out of a fear of self-destruction) was a story that was shared by numerous leading voices that represent the Sikh way of life. Again on the face of it the wording seemed harmless enough, but to a discerning more critical eye it was not only dangerous, but disrespectful and at the time of year that it was published, quite despicable. The story suggested that a potential victim of rape had been spared when walking down an alleyway because at the moment she encountered the potential criminal, she began reciting Gurbani. The story continued that the next day upon hearing that a crime of rape had indeed taken place in that same alleyway sometime after she had walked through, the could-have-been victim visited the local Police Station to ask the rapist why she had been spared. He declared to her that she was his intended victim at first, but each time he ventured towards her in the alleyway, 2 turbaned men stood in his path preventing him from moving forward. Leaving aside the clear and obvious fallacies in this story, the idea being represented that God physically protects those who pray is not consistent with Sikh ideology. The Guru taught that it is up to the individual to shape the World and that reliance on a higher being or other-Worldly powers were not in accordance with the laws of the Universe. What troubled me most about this story was that it was published when Sikhs were commemorating the 30th anniversary of the invasion of the Darbar Sahib in Amritsar – a time when numerous acts of criminality were perpetrated. This story and the ideas presented in it, whilst apparently harmless and in good faith, ridiculed the thousands of people who were caught up as part of the Indian Government’s collateral damage, many of whom would have been praying for a rescue that did not come. Were their prayers less pure than those of the would-be victim of the rapist from the Facebook story? Or beyond that, should Sikh women who fear rape at any point in their lives rest easier knowing that if they recite Gurbani they will be saved?

It was not the story itself – which by the way is a cheap attempt to fear-monger, paraded by charlatans of many different faiths and traditions – which irritated me as much as the countless Sikhs who proudly ‘liked’, ‘shared’ and copiously commented all over it. There was no attempt to think through just what was being stated here; there was instead acres of blind sheep grazing on the viral goodness that came with associating themselves to their Sikh ‘faith’. Facebook is not to be blamed for the inpetitude of the masses, but it is to be blamed for making it easy for individuals to express themselves without actually expressing themselves… through clicking a button. We, the user, are responsible for what we do with social media and I found myself that day remembering the ‘RIP’ comments, thinking why are Sikhs not considering just what this story is that they’re sharing, about the words that have been used? No sooner had I answered that question, than I wrote my final status and logged off. I’m pretty certain Facebook won’t miss me, but I’m damn sure I’ve not been missing it.